Neuroscience Research Notes

ISSN: 2576-828X

OPEN ACCESS | RESEARCH NOTES

Translation, reliability, and structural validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the general population of Mongolia

Enkhnaran Tumurbaatar 1,2, Tetsuya Hiramoto 3, Gantsetseg Tumur-Ochir 4, Oyunsuren Jargalsaikhan 5, Ryenchindorj Erkhembayar 2, Tsolmon Jadamba 6,7*, Battuvshin Lkhagvasuren 1,8*

1 Brain Science Institute, Graduate School, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

2 Department of International Cyber Education, Graduate School, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

3 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Fukuoka National Hospital, National Hospital Organization, Fukuoka, Japan.

4 Department of Mental Health, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

5 Department of Psychology, University of the Humanities, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

6 Timeline Research Center, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

7 Center of Excellence in Brain Research, Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

8 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare Narita Hospital, Narita, Chiba, Japan.

* Correspondence: battuvshin@mnums.edu.mn; Tel.: +976-99192738

Received: 5 July 2021; Accepted: 4 October 2021; Published: 24 November 2021

Edited by: King-Hwa Ling (Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia)

Reviewed by: Wael Mohamed (Menoufia Medical School Shebin El Kom, Egypt); Suchat Paholpak (Khon Kaen University, Thailand)

https://doi.org/10.31117/neuroscirn.v4i3Suppl.101

ABSTRACT

Various psychological, biological, and social factors make people vulnerable to mental health problems. These precursory factors as mental distress, are not sufficient alone for diagnosing a mental disorder but are recognised as risks to mental health. There has been no screening tool available in Mongolia that is adequately validated for mental health screening and neuropsychiatric functions of the brain. Therefore, we aimed to translate and validate the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) to identify potential mental distress in healthy people. The HADS is reliable, valid, and practical for identifying the most common psychological disturbances. This nationwide comparative observational study for the validity of a self-reported measure was conducted between June and December 2020. One thousand ninety-four participants were randomly selected, aged 13-75, mean age was 37.7±13.7 years old, 60.9% were females, 63.9% were married. HADS total score was 13.0±5.7, HADS anxiety (HADS-A) score was 6.8±3.6, and HADS depression (HADS-D) score was 6.0±3.1 for the original two-factor model. The external reliability was good in the whole scale, and both subscales using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (0.872, 0.837, and 0.801 for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D, respectively). Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.776, 0.756, and 0.582, respectively, for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D, indicating an acceptable internal consistency for the entire scale but marginal reliability for the HADS-D subscale. The reliability of both the two-factor and three-factor structures of the HADS was confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis with a satisfactory model fit on a separate sample. In conclusion, the Mongolian version of the HADS can be considered a valid and reliable measurement tool for various scientific and clinical practices in the general population.

Keywords: validation study; confirmatory factor analysis; Mongolia; general population; Mon-TimeLine;

©2021 by Tumurbaatar et al. for use and distribution according to the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

In the last few decades, following the rapid technological development and the high burden of society’s needs, the mental distress in the general population has been increasing steadily. National Center for Health Statistics reported that the prevalence of a major depressive episode was 7.6% in the USA (Pratt & Brody, 2004). In 2018, over 200 million people in the world were affected by major depressive disorder, and generalised anxiety disorder was the most prevalent (16.7% -21.2%) of the mental disorders examined across all countries (Auerbach et al., 2018). In Mongolia, the last report on the prevalence of mental disorders in the general population suggested that the overall prevalence of mental disorders among the population was 1.8% (Byambasuren & Tsetsegdary, 2018), which was conducted between 1976 and 1984. Various psychological, biological, and social factors make people vulnerable to mental health problems. These precursory factors, also known as mental distress, are not sufficient for the clinical diagnosis of a mental disorder but are recognised as risk factors to mental health. They have significant comorbidity with chronic medical disorders and are a risk factor for exacerbation and mortality (Dudeney et al., 2017; Ozdin & Bayrak Ozdin, 2020). Assessing and identifying the individual’s anxiety and depression is a proper way to prevent severe mental distress in one’s life.

There is an urgent need in determining the current mental health issues in the general population. At the same time, it is essential to validate screening tools. There are several series of screening tools/instruments across the world. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) is a frequently used assessment tool that is reliable, valid, and practical for identifying these two most common psychological disturbances (Herrmann, 1997) in the primary care unit (Cavanaugh et al., 1983) and in the general population (Herrero et al., 2003; Iani et al., 2014). The HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983 (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) and is a cost-effective, easy-to-administer, and well-practised scale. The survey consists of 14 items that further extend to the Anxiety subscale and Depression subscale, each with seven items.

One problem with using the HADS is that the cut-off point suggested in the original article of the scale by Zigmond and Snaith may not be valid when used cross-culturally (Bjelland et al., 2002). The 2-factor structure was confirmed in many studies (Mykletun et al., 2001), but studies also found that 1-factor (Johnston et al., 2000), and 3-factor (Desmond & Maclachlan, 2005) structures. Thus, the difficulties associated with the discrepancy between the optimal cut-off and the factor structures of HADS are increasingly revealed.

HADS has been translated into many languages around the world. There has been no available Mongolian version of the HADS that was adequately translated and validated. Therefore, we aimed to validate and evaluate the factor structure of the HADS to identify potential mental distress in the general population of Mongolia.

2.0 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study Design and population

This comparative observational study for the validity of a self-reported measure was conducted between June and December 2020. It is a nested validation study within a nationwide multicenter, interdisciplinary, prospective, population-based “Mon-TimeLine” cohort study to investigate brain-related disorders in the general population of Mongolia. The current population of Mongolia is 3,296,866 in 2019, based on the National Statistical Office of Mongolia, of which half of them live in Ulaanbaatar, the capital city, and the remaining half of them live in 4 rural regions (NSO, 2020). The Mon-TimeLine cohort was designed using a multi-stage cluster sampling. At the first stage, we randomly selected the primary sampling units based on the regions of the country. There are four geographical regions in Mongolia included 5-6 prefectures or geopolitical units in each region. The capital city Ulaanbaatar and the nine prefectures were Gobi-Altai, Khovd (Western region), Uvurkhangai, Arkhangai (Mountain region), Tuv, Dornogobi (Central region), Dornod, Sukhbaatar, and Khentii (Eastern region). In the second stage, the 64 sampling centres, including 38 primary health centres of 8 districts in Ulaanbaatar and 26 primary health centres of 4 rural regions in Mongolia. Primary health centres provide health care services to all individuals within specific geopolitical units where the entire population is registered by name, age, gender, education, employment, and household income.

Participants who lived in the administrative units for at least 6 months, were literate in Cyrillic Mongolian language, and were not admitted to any clinical setting were considered to meet inclusion criteria. Participants who could not read and understand scale items, generally not able to answer the scale independently were excluded. We randomly selected 20 individuals from each sampling centre. If participants were not available at the centre for the paper-based questionnaire assessment, they were replaced by the following available participants regardless of age and sex category.

2.2 The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale

The HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith to identify cases of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression among patients in nonpsychiatric hospital clinics. The questionnaire consists of 14 items, seven of them are for anxiety (HADS-A), and the remaining seven are for depression (HADS-D) formulated in a readily understandable language. Individuals might feel tested for certain mental disorders; thus, any symptoms of severe psychopathology are not included intending to increase acceptability and preclude. This makes HADS more sensitive to milder psychopathology. The ranges of scores for cases on each subscale are 0–7 or normal, 8–10 or mild disorder, 11–14 or moderate disorder, and 15–21 or severe disorder (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). Mongolian translation of the HADS was carried out through several steps: an initial forward translation (from English to Mongolian) by two independent translators with a background in linguistics and neuroscience research, the pilot questionnaire was distributed to 17 participants, a back-translation (from Mongolian to English), and finally a consensual version to check against the original HADS by the expert committee. Discrepancies were discussed, and agreement was achieved.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The normality of the data distribution was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test. The study characteristics were expressed as means with a standard deviation for normally distributed variables and as numbers with percentages in cases of categorical data. The differences between groups were compared using the Student’s T-test for continuous variables. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the difference between means of HADS total and subscales scores according to groups of variables.

Internal consistency of the HADS was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha. For the external reliability, a test-retest procedure was carried out with an interval of 16.3±1.7 days between two-time points. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to determine its test-retest reliability, both overall and for each subscale, for external reliability. We used ICC values of <0.5, <0.75, <0.9, and >0.9 as indicators for poor, moderate, good, and excellent reliability, respectively, following the analysis used by Koo TK et al. (Koo & Li, 2016).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using the principal component analysis with varimax rotation, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of sampling adequacy over 0.5 at a significance level of the Bartlett test of Sphericity below 0.05, the number of relevant factors via eigenvalue>1 were retained for rotation (Cattell, 1966). A factor loading over 0.4 was chosen as satisfactory. As an additional analysis to supplement component structure, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using IBM SPSS AMOS. The 3-factor of the Mongolian version of the HADS and the original 2-factor model fit was assessed using the chi-square test statistic and the following criteria for the structural equation modeling: goodness-of-fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI) close to 0.90 or above, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) close to 0.06 or below (Brown, 2006).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The institutional review board and Ethics committee of the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (MNUMS) approved the study protocol and procedures for informed consent (Ethics number: 2020/03-05).

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic characteristics of the study participants by HADS total score and subscales scores

We initially collected 1,436 participants, whereas 135 (9.4%) participants refused to participate. 207 (14.4%) participants who could not read and understand scale items or generally answer the scale were excluded. 1,094 (76.2%) subjects were enrolled for this analysis (Figure 1). The mean age of participants was 37.7±13.7 years, age ranged between 13-75 years, 666 (60.9%) were women, 615 (56.2%) were residents out of the Ulaanbaatar city, 699 (63.9%) were married, and 800 (73.1%) had education below Bachelor’s degree. 559 (51.1%) were employed, but 716 (65.5%) had low income.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the study participants (A). The required sample size was 1280. Of 1436 participants were included, whereas 135 participants refused to participate. Data from 1094 participants were used in the present analysis—Mon-TimeLine Cohort centres across Mongolia (B). The cohort consists of 64 sampling centres, including 38 primary health centres of 8 districts in Ulaanbaatar and 26 primary health centres of 4 rural regions in Mongolia.

3.2 Exploratory factor analysis

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the HADS items. Table 2a showed the factor pattern matrix when the exploratory factor analysis was applied to the correlation matrix from the 14 items of the HADS. The number of factors was evaluated using the eigenvalue criteria (number of eigenvalues > 1) and Cattell’s screen test. EFA using the Varimax rotation and maximum likelihood extraction method was used to identify the underlying dimensions of the 14 items. The results of the EFA indicated a three-factor solution with eigenvalues of 3.8, 1.6, and 1.1. The first factor was labelled ‘HADS-A’, the second factor was labelled ‘HADS-D1’, and the third factor was labelled HADS-D2. Items with component loadings ≥ 0.40 on the structure component were retained. The factors together explained 46.97.% of the total variance. Keiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) and significance of the Bartletts test results were 0.859 and <0.001. Because HADS had been originally used in a Two-Factor Structure, HADS-A and HADS-D, we analysed the 2-factor matrix according to the HADS Original (Table 2b). However, the factor loading was lower than 0.4, indicating the two-factor structure is not better than the three-factor model.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the HADS

Items | Mean | ±SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

HADS1. I feel tense or ‘wound up’ | 0.96 | ±0.68 | 0.546 | 0.803 |

HADS2. I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy | 0.73 | ±0.80 | 0.984 | 0.509 |

HADS3. I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen | 1.19 | ±0.91 | 0.323 | -0.725 |

HADS4. I can laugh and see the funny side of things | 1.03 | ±0.79 | 0.388 | -0.347 |

HADS5. Worrying thoughts go through my mind | 1.09 | ±0.86 | 0.479 | -0.365 |

HADS6. I feel cheerful | 0.84 | ±0.93 | 0.698 | -0.693 |

HADS7. I can sit at ease and feel relaxed | 0.93 | ±0.93 | 0.448 | -1.062 |

HADS8. I feel as if I am slowed down | 1.09 | ±0.74 | 0.525 | 0.319 |

HADS9. I get a sort of frightened feeling like ‘butterflies’ in the stomach | 0.94 | ±0.83 | 0.598 | -0.191 |

HADS10. I have lost interest in my appearance | 0.98 | ±0.97 | 0.623 | -0.699 |

HADS11. I feel restless as I have to be on the move | 0.78 | ±0.74 | 0.853 | 0.758 |

HADS12. I look forward with enjoyment to things | 0.50 | ±0.71 | 1.370 | 1.449 |

HADS13. I get sudden feelings of panic | 0.95 | ±0.67 | 0.581 | 0.990 |

HADS14. I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV program | 0.81 | ±0.83 | 0.826 | 0.104 |

HAD-Total | 13.0±5.7 | |||

Table 2a: The result of exploratory factor analysis for 3-factor structure of the Mongolian version of HADS

Items | HADS-A | HADS-D1 | HADS-D2 | Communalities |

HADS5. Worrying thoughts go through my mind | 0.739 | 0.143 | 0.042 | 0.569 |

HADS1. I feel tense or ‘wound up’ | 0.736 | 0.120 | 0.061 | 0.559 |

HADS3. I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen | 0.726 | 0.145 | 0.082 | 0.555 |

HADS13. I get sudden feelings of panic | 0.644 | -0.056 | 0.250 | 0.481 |

HADS8. I feel as if I am slowed down | 0.578 | 0.027 | 0.285 | 0.416 |

HADS9. I get a sort of frightened feeling like ‘butterflies’ in the stomach | 0.495 | 0.514 | -0.199 | 0.548 |

HADS11. I feel restless as I have to be on the move | 0.489 | -0.105 | 0.464 | 0.466 |

HADS2. I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy | 0.009 | 0.722 | -0.100 | 0.531 |

HADS12. I look forward with enjoyment to things | 0.139 | 0.640 | 0.286 | 0.511 |

HADS7. I can sit at ease and feel relaxed | 0.287 | 0.508 | 0.167 | 0.368 |

HADS4. I can laugh and see the funny side of things | -0.175 | 0.431 | 0.395 | 0.373 |

HADS14. I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV program | -0.028 | 0.405 | 0.359 | 0.294 |

HADS6. I feel cheerful | 0.220 | 0.170 | 0.615 | 0.456 |

HADS10. I have lost interest in my appearance | 0.208 | 0.065 | 0.633 | 0.449 |

Total variance explained | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

Table 2b: The result of exploratory factor analysis for the 2-factor structure of the Mongolian version of HADS

Items | HADS-A | HADS-D | Communalities |

HADS1. I feel tense or ‘wound up’ | 0.720 | 0.078 | 0.525 |

HADS3. I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen | 0.716 | 0.110 | 0.525 |

HADS5. Worrying thoughts go through my mind | 0.718 | 0.093 | 0.524 |

HADS7. I can sit at ease and feel relaxed | 0.307 | 0.512 | 0.356 |

HADS9. I get a sort of frightened feeling like ‘butterflies’ in the stomach | 0.406 | 0.370 | 0.302 |

HADS11. I feel restless as I have to be on the move | 0.601 | 0.032 | 0.362 |

HADS13. I get sudden feelings of panic | 0.690 | -0.010 | 0.476 |

HADS2. I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy | -0.040 | 0.636 | 0.406 |

HADS4. I can laugh and see the funny side of things | -0.072 | 0.556 | 0.314 |

HADS6. I feel cheerful | 0.376 | 0.362 | 0.271 |

HADS8. I feel as if I am slowed down | 0.633 | 0.084 | 0.408 |

HADS10. I have lost interest in my appearance | 0.373 | 0.271 | 0.212 |

HADS12. I look forward with enjoyment to things | 0.194 | 0.688 | 0.511 |

HADS14. I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV program | 0.060 | 0.507 | 0.261 |

Total variance explained | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.11 |

3.3 Examining the goodness-of-fit factor model

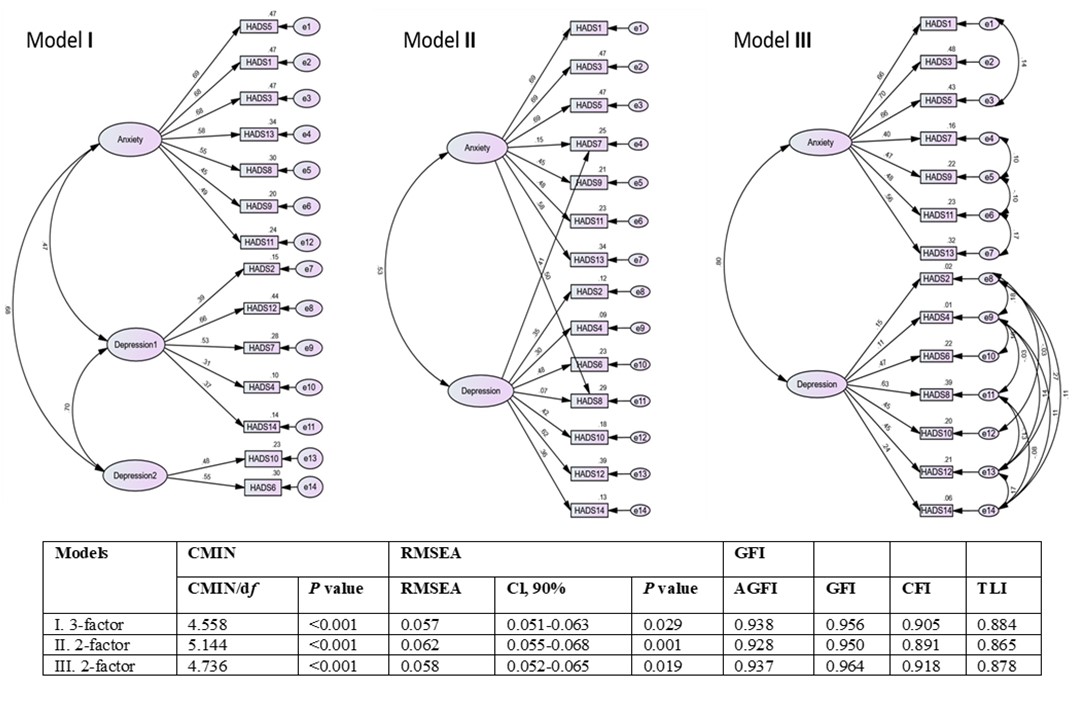

We next conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to find the goodness-of-fit factor model of the Mongolian version of the HADS (Figure 2). The three-factor model, model I, showed a good model fit. The factor loadings ranged between 0.489 and 0.739 for HADS-A, between 0.405 and 0.722 for HADS-D1, and between 0.613 and 0.633 for HADS-D2. The RMSEA was 0.057, CFI was 0.905, and TLI was 0.884.

The two-factor model, Model II, did not yield an adequate model fit because the RMSEA of this model was 0.062, CFI was 0.891, and TLI was 0.865. Based on the modification index and recent research (Patrick & Deyo, 1989), items 7 and 8 were allowed to cross-load on both factors in this model.

Furthermore, we proposed the third model that could be improved by allowing correlations between the error variances, items, factors, and inter-items. The RMSEA was 0.058, CFI was 0.964, and TLI was 0.878 in this model. The unifying structure of 2-factor and 3-factor models was assessed using the summary of fitting indices asχ2/df < 5, CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08 as a good fit. These findings indicate that models I and III were well-fitted models.

Figure 2: Confirmatory factor analysis path diagram. Rectangles indicate measured variables, and large ellipses represent subscales. Covariances of errors between items with similar content are shown.

3.4 Reliability

Table 3 shows the results of examining the reliability. A test-retest study was carried out on 80 participants—16.3±1.7 days between 2 time-points. Participants aged between 18 and 29 years, mean age was 20.8±1.9 years, 43 (53.8%) were males.

The ICC value in model I was 0.872, 0.833, and 0.752, whereas Cronbach’s alpha was 0.776, 0.784, and 0.608, respectively, for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D1+D2. In contrast, the ICC value was 0.872, 0.837, and 0.801, whereas Cronbach’s alpha was 0.776, 0.756, and 0.582, respectively, for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D in Model III. The agreement between the measures was good with a similar standard error of the means. Based on these results, we calculated the scores in Models I and III (Table 4).

In model I, the mean value was 13.0±5.7, 7.0±3.6, and 5.8±3.3, respectively, for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS D1+D2. In contrast, in Model III, the mean value was 13.0±5.7, 6.8±3.6, and 6.0±3.1, respectively, for the HADS-T, HADS-A, and HADS-D. In the original HADS, a score ≥ 8 is used as the cut-off value for detecting anxiety and depression. In this study (Two-Factor Structure, Model III), the proportion of subjects showing anxiety (scoring 8 or more points in HADS-A) was 473 (43.2%), and depression (scoring 8 or more points in HADS-D) was 337 (30.8%).

Table 3: The result of examining reliability on each factor model

| HADS | External reliability Test-retest, n=80 ICC | Internal consistency, n=1094 Cronbach’s a |

3-factor model | HADS-A | 0.833 | 0.784 |

HADS-D1 | 0.712 | 0.413 | |

HADS-D2 | 0.597 | 0.560 | |

HADS D1+D2 | 0.752 | 0.608 | |

HADS-T | 0.872 | 0.776 | |

2-factor model | HADS-A | 0.837 | 0.756 |

HADS-D | 0.801 | 0.582 | |

HADS-T | 0.872 | 0.776 |

ICC (Intraclass correlation coefficient)

Table 4: The result of HADS-A and HADS-D

| HADS | Mean | ±SD |

3-factor model | HADS-A | 7.0 | ±3.6 |

HADS-D1 | 4.0 | ±2.5 | |

HADS-D2 | 1.8 | ±1.5 | |

HADS D1+D2 | 5.8 | ±3.3 | |

HADS-T | 13.0 | ±5.7 | |

2-factor model | HADS-A | 6.8 | ±3.6 |

HADS-D | 6.0 | ±3.1 | |

HADS-T | 13.0 | ±5.7 |

4.0 DISCUSSION

We investigated the reliability and validity of the HADS Cyrillic Mongolian version in Mongolia. External reliability was good in the whole scale, and both subscales used ICC. A Cronbach’s α for the whole scale, for the subscales (with relatively low reliability for HADS-D subscale), suggested that the questionnaire can be considered a sufficiently homogenous reliable measurement tool. The reliability of both the 2-factor and 3-factor structure of the HADS was confirmed using CFA with a satisfactory model fit on a separate sample. These findings suggest satisfactory internal validity and potentially favourable construct or external validity.

Although HADS is an extensively used, well-recognised measure for anxiety and depression scale in many countries, cross-cultural validity and adaptation are crucial concepts for translation in countries where English is not spoken widely (Maters et al., 2013). Finnish translation of HADS has been conducted with two other instruments for cross-cultural validation and external previously validated measures (Aro et al., 2004). SF-36v2 is a commonly used health status self-report measure that is prevalently used as an external validity tool for other tools, including HADS, and previous Mongolian versions have been validated (Nakao et al., 2016). However, we were not able to incorporate licensed instruments in the study. Indian Punjabi translation of the HADS scale was reported, and linguistic equivalency was determined among bilingual subjects of Punjabi and English (Lane et al., 2007). We were not able to include this step due to limitations in the availability of abundant fluent bilinguals. Experts committee evaluations determined that the Mongolian translation had satisfactory cultural and linguistic properties in our study, requiring minimal adaptation. Translation and back-translation steps resolved all discrepancies accordingly.

In the current study, the psychometric properties of the HADS have been assessed in the general population of Mongolia. In this study, we found two good models; the original bifactor model and the 3-factor model with cross-loadings of items 7, and 8, which are repeatedly referred to in previous studies, underweighted loading on the subscales which assumed to belong (Bocerean & Dupret, 2014). Although we can use the original version, we need to take into account the characteristics of the Mongolian version when we use subscales: HADS-A and HADS-D. In our three-factor model items, 4 and 10 separated from the integrated depression subscale. For anxiety screening, it might be a better way to use items 1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 13 for subscale HADS-A, for depression screening items 2, 4, 7, 12, 14, 6, and 10 interpreted as a sum of subscale HADS-D1 and HADS-D2. Item 7, initially included in the anxiety subscale, was loaded with a significantly higher value in the depression subscale factor. Several studies mentioned the cross-loading of item 7 (Chan et al., 2010; Djukanovic et al., 2017), which was considered poor (Cosco et al., 2012) but most likely to transitional item. Some authors highlighted that item 7 loads on both subscales because it refers to psychomotor agitation “cannot sit at ease” and anhedonia domain “cannot feel relaxed” of depression (Dunbar et al., 2000; Matsudaira et al., 2009). Similar to mentioned above, item 8 originally included in the depression subscale had good loading weight on the anxiety subscale compared to the depression subscale, which had also been repeatedly reported (Cosco et al., 2012; Djukanovic et al., 2017). Item 8 “Slowed down” may not be interpreted as a depressive symptom, which means slows down from fatigue (Johnston et al., 2000), in the Mongolian version, “slowed down” is translated more like to have the meaning of “feeling sleepy or dull from the heat or tiredness” which may lead to more misunderstanding. Item 9 is a British idiom, such as “butterflies in the stomach”, which causes trouble and inaccuracy when translating into Mongolian. However, it did not show any problematic factor loadings in the present study. Therefore, translated versions of HADS need to be revised according to the language and culture of the specific population to facilitate cross-cultural adaptation.

The depression subscale only includes 4 of the dozen diagnostic symptoms of the major depressive disorder by ICD-10 (World Health, 1992). Based on a few pieces of evidence, the somatic symptoms of patients in the general practice are not reliable indicators of depression (Coyne & van Sonderen, 2012), their patients had higher scores than psychiatric patients using standard assessment tools (Mitchell et al., 2010; Thombs et al., 2010). These data contraindicate the theory behind HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983).

Many studies validated the HADS using component and factor analysis found the first unrotated factor included more than a half of the total items (Herrmann, 1997), the bifactor model and Dunbar’s high-order model were considered understandable solutions in the presence of a solid general factor (Norton et al., 2013). Moreover, it is difficult to distinguish between anxiety and depression; they are usually comorbid and have identical symptoms (Watson, 2005). When having a common one factor and a moderate correlation between subscales anxiety and depression, it has been recommended that HADS be used to measure overall mental distress rather than anxiety or depression separately.

Numerous translations, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of HADS into other languages than English have been reported globally. Wiglusz et al. demonstrated external validity of the HADS Polish version for screening anxiety with DSM-diagnosis-based clinical setting (Wiglusz et al., 2018). In future studies, the external validity of the HADS Mongolian version should identify potential sensitivity and specificity for clinically screening for anxiety and depression. Similar to our study, translation and reliability analyses have been carried out in Persian and Arabic versions and have both reported higher psychometric values (Montazeri et al., 2003). The Mongolian language is a distinct language belonging to the Altaic language family that is spoken in Mongolia. People’s Republic of China’s Inner Mongolia region, and Russian Federation’s republics. In the following investigations, field trials of the Mongolian versions in different countries and regions could be potentially carried out. Mongolia is a developing country with a higher literacy rate, and we investigated reliability in both urban and local settings. Therefore, the current translation can be potentially applied to future researches in rural and urban Mongolia.

4.1 Limitations

Our main limitation was the absence of further construct validity measures in this study to investigate related aspects and factors further. In addition, the current study includes all potential limitations of self-reported measures.

5.0 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that the Mongolian version of HADS has good internal consistency, and construct validity was favorable. Both 2-factor and 3-factor structures of the HADS were satisfactory models fit on a separate sample. In conclusion, the Mongolian version of HADS is a valid and reliable measurement tool for mental health screening in the general population.

Author Contributions

T.H., B.L., and T.J. conceived and designed the study; E.T., and G.T. performed and collected the data; E.T., G.T., and O.J. analysed the data; T.J., and B.L. contributed reagents and materials; E.T., O.J., and R.E. wrote the paper; T.H. and B.L. reviewed and edited the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Aro, P., Ronkainen, J., Storskrubb, T., Bolling-Sternevald, E., Svardsudd, K., Talley, N. J., . . . Agreus, L. (2004). Validation of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation into Finnish of the abdominal symptom questionnaire, the hospital anxiety and depression scale and the complaint score questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 39(12), 1201-1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520410008132

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., . . . Kessler, R. C. (2018). WHO World Mental Health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623-638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3

Bocerean, C., & Dupret, E. (2014). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a large sample of French employees. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0354-0

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research., New York, NY, US.

Byambasuren, S., & Tsetsegdary, G. (2018). Mental health in Mongolia. International Psychiatry, 2(8), 9-12. https://doi.org/10.1192/S1749367600007207

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The screen test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245-276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

Cavanaugh, S., Clark, D. C., & Gibbons, R. D. (1983). Diagnosing depression in the hospitalised medically ill. Psychosomatics, 24(9), 809-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(83)73151-8

Chan, Y. F., Leung, D. Y., Fong, D. Y., Leung, C. M., & Lee, A. M. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a large community sample of adolescents in Hong Kong. Quality of Life Research 19(6), 865-873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9645-1

Cosco, T. D., Doyle, F., Ward, M., & McGee, H. (2012). Latent structure of the Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale: a 10-year systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(3), 180-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.06.008

Coyne, J. C., & van Sonderen, E. (2012). No further research needed: abandoning the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(3), 173-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.12.003

Desmond, D. M., & Maclachlan, M. (2005). The factor structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in older individuals with acquired amputations: a comparison of four models using confirmatory factor analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 20(4), 344-349. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1289

Djukanovic, I., Carlsson, J., & Arestedt, K. (2017). Is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) a valid measure in a general population 65-80 years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0759-9

Dudeney, J., Sharpe, L., Jaffe, A., Jones, E., & Hunt, C. (2017). Anxiety in youth with asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatric Pulmonology, 52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23689

Dunbar, M., Ford, G., Hunt, K., & Der, G. (2000). A confirmatory factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale: comparing empirically and theoretically derived structures. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 39(1), 79-94. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466500163121

Herrero, M. J., Blanch, J., Peri, J. M., De Pablo, J., Pintor, L., & Bulbena, A. (2003). A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in a Spanish population. General Hospital Psychiatry 25(4), 277-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00043-4

Herrmann, C. (1997). International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42(1), 17-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4

Iani, L., Lauriola, M., & Costantini, M. (2014). A confirmatory bifactor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in an Italian community sample. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-84

Johnston, M., Pollard, B., & Hennessey, P. (2000). Construct validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale with clinical populations. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 48(6), 579-584. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00102-1

Kanmaniraja, D., Le, J., Hsu, K., Lee, J. S., McClelland, A., Slasky, S. E., . . . Ricci, Z. J. (2021). Review of COVID-19, part 2: Musculoskeletal and neuroimaging manifestations including vascular involvement of the aorta and extremities. Clinical Imaging, 79, 300-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.08.003

Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Lane, D. A., Jajoo, J., Taylor, R. S., Lip, G. Y., Jolly, K., & Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation Steering, C. (2007). Cross-cultural adaptation into Punjabi of the English version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-7-5

Maters, G. A., Sanderman, R., Kim, A. Y., & Coyne, J. C. (2013). Problems in cross-cultural use of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: “no butterflies in the desert”. PLoS One, 8(8), e70975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070975

Matsudaira, T., Igarashi, H., Kikuchi, H., Kano, R., Mitoma, H., Ohuchi, K., & Kitamura, T. (2009). Factor structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Japanese psychiatric outpatient and student populations. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-42

Mitchell, A. J., Meader, N., & Symonds, P. (2010). Diagnostic validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in cancer and palliative settings: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord, 126(3), 335-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.067

Montazeri, A., Vahdaninia, M., Ebrahimi, M., & Jarvandi, S. (2003). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-14

Mykletun, A., Stordal, E., & Dahl, A. A. (2001). Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 540-544. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.6.540

Nakao, M., Yamauchi, K., Ishihara, Y., Solongo, B., Ichinnorov, D., & Breugelmans, R. (2016). Validation of the Mongolian version of the SF-36v2 questionnaire for health status assessment of Mongolian adults. Springerplus, 5, 607. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2204-7

Norton, S., Cosco, T., Doyle, F., Done, J., & Sacker, A. (2013). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: a meta confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74(1), 74-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.10.010

NSO. (2020). Population of Mongolia In National Statistical Office. National Statistical Office. https://www.1212.mn//Stat.aspx?LIST_ID=976_L03&type=tables

Ozdin, S., & Bayrak Ozdin, S. (2020). Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(5), 504-511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020927051

Patrick, D. L., & Deyo, R. A. (1989). Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Medical Care, 27(3 Suppl), S217-232. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018

Pratt, L. A., & Brody, D. J. (2014). Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009-2012. NCHS Data Brief (172), 1-8.

Thombs, B. D., Ziegelstein, R. C., Pilote, L., Dozois, D. J., Beck, A. T., Dobson, K. S., . . . Abbey, S. E. (2010). Somatic symptom overlap in Beck Depression Inventory-II scores following myocardial infarction. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(1), 61-66. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076596

Watson, D. (2005). Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: a quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 522-536. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522

Wiglusz, M. S., Landowski, J., & Cubala, W. J. (2018). Validation of the Polish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for anxiety disorders in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 84, 162-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.010

World Health, O. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. In. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Help us to sustain this free open access journal via a voluntary contribution today.

Your contribution will make sure that reading, submitting articles, publishing and indexing of all scientific materials in this journal remain free of charge for everyone.